Eight years ago, as part of my Masters study at the RWCMD, I undertook a research project into nineteenth-century British flute music. My starting point was that some must have been written but nothing remained in the repertoire, so I was keen to find out what had been composed, who played it where, and why had it been forgotten – was it just not very good, or was it all a bit more complicated than that? My investigations took me to the British Library reading rooms where I spent many happy hours studying nineteenth-century concert programmes, old flute tutor books and journals, tracking down the repertoire when I could and contextualising it all with biographical and historical research. I fell in love with the world of nineteenth-century British music studies and with nineteenth-century Britain, savouring the glimpse provided by annotations and anecdotes into how people were experiencing this music and concert life two hundred years ago. It is thanks to this research project that I am now undertaking my PhD.

But to return to the world of the nineteenth-century flute, in the dim and distant past of 2009 the BL did not allow people to take photos in their archives and the costs of using their copying facilities were prohibitive. I found myself in the frustrating position of having identified hundreds of interesting pieces but I could not afford to actually play them, with the exception of the rather lovely Suite by Edward German which I had obtained from another source. I wrote up my dissertation and moved on to projects new, keeping in mind a hope I could return to this music some day. The opportunity presented itself in a course of lectures I was requested to give to the Glossop Guild in November/December 2016 on music in nineteenth-century Britain. I immediately decided to make one of these a lecture-recital about nineteenth-century British flute culture. Given the new photography rules at the BL I planned a visit, but first contacted Robert Bigio, the flute maker and researcher into nineteenth-century British flutes, to see if he was still happy to lend me some of his music as he had very kindly offered several years ago. He was, so off I drove to north London. He hauled several large cardboard boxes out of his shed, music given to him by the granddaughter of a flautist active at the end of the nineteenth century. ‘Take them away!’ he said. ‘I haven’t even had the chance to look through them properly and they are taking up lots of space!’ We filled my boot with music, which is currently occupying my loft until I get a chance to catalogue, copy and return it.

The photograph of music accompanying this post is the first recital programme of nineteenth-century British flute music I have devised, from this collection supplemented by other sources. I have now presented it twice, first in the context of a lecture-recital in Glossop, then in a shortened format at the Wesley Chester recital series in February 2017. It is the tip of a very exciting iceberg – I was confident that much of the music I had discovered could work well in a recital programme, whether as great music in its own right, or whether as interesting pieces when framed and contextualised appropriately. Presenting it to a general audience has confirmed this perception and several of the pieces have appeared in other recitals I have given since.

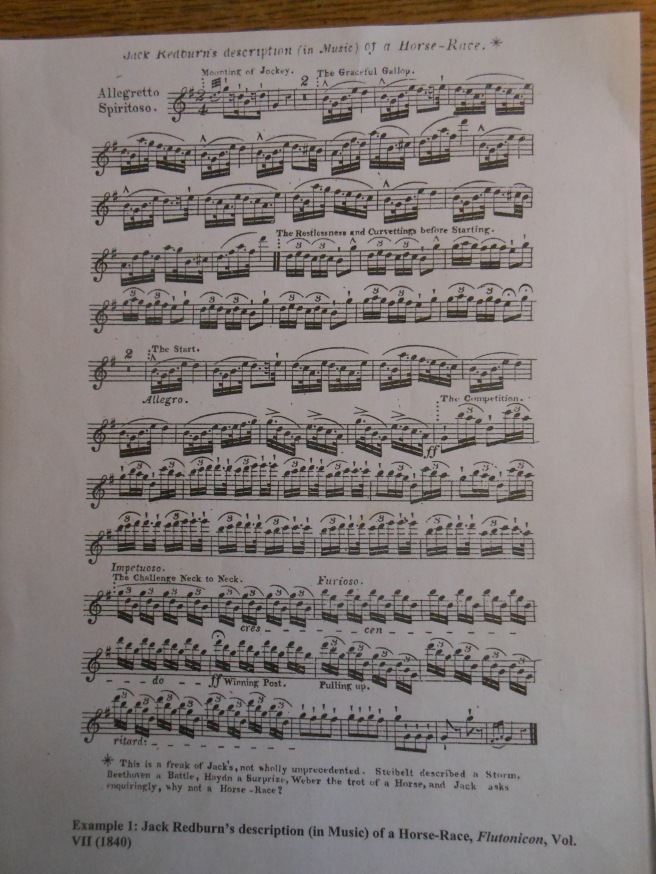

The stories behind this music, its composers, its performers and audiences are worth telling, ranging from pistols at dawn to not altogether honourable courting practices, but they deserve their own post. For this one I will confine myself to a brief account of this recital programme. It is approximately chronological, with several distinct groupings of repertoire style. The first, by W. N. James, an amateur flute playing who published extensively, is very much intended for use in the home – an image of this piece is below, and you can picture the gentleman brandishing his flute in front of his friends saying ‘look what was in the Flutonicon this week!’. It was James who met to duel with Charles Nicholson, the preeminent flautist in Britain at that time, after a series of increasingly heated exchanges by letter and in print. They were arrested to keep the peace. Nicholson’s piece here is one of his more virtuosic sets of variations, compared to others he wrote intended more for the domestic market. It is rather difficult but a lot of fun. The compositions by Prout, Barnett and Macfarren, all serious composers held in high esteem in their day, are the results of efforts by the flute makers and publishers Rudall, Carte & Co. to encourage and commission sonatas and similar genres for the flute, published in their Flute Player’s Journal and the Journal of the London Society of Amateur Flute Players who assisted in the cause. There is some very appealing music within these pages, and the Barnett Sonata has now been reissued in a modern edition so I am evidently not the only person to think so! Edward de Jong was the first principal flute of the Hallé Orchestra, giving at least 13 solos at Hallé concerts between 1858 and 1865, several of which were his own compositions. This caprice is very well written and sounds much harder than it is! Edward German, best remembered today for Merrie England, wrote his Suite for the Welsh flautist Frederick Griffith, perhaps the most sought-after flautist in 1890s London. Griffith premiered it in Steinway Hall in 1892, with German accompanying. The Romance by Dora Bright was also composed for Griffith, with whom she had a close friendship. Finally, as it was nearly December when we gave this recital, we concluded with a rather wonderful set of variations on ‘Adeste Fidelis’ by Dipple, a contemporary of Charles Nicholson. All these pieces have met with a warm reception from our audiences.

W. N. James Jack Redburn’s description (in music) of a horse race (1840)

Charles Nicholson (1795-1837) Au Clair de la Lune: Introduction, Theme & Variations

Ebenezer Prout (1835-1909) Sonata Op. 17 (1883)

1: Allegro con anima

2: Romanza

John F Barnett (1837-1916) Grand Sonata

1: Allegro

W. A. Macfarren (1813-1887) Recitative and Air (1883)

Edward de Jong (1837-1920) Caprice “Will o’ the Wisp” (1899)

Edward German (1862-1936) Suite for Flute and Piano (1892)

1: Valse Gracieuse

Dora Bright (1862-1951) Romance and Seguidilla (1891)

T. J. Dipple Variations on “Adeste Fideles”